We are living in a period swamped with literary fiction. The stocked shelves of bookstores and BookTok doom-scrolling all point to its dominance, specifically in the cult of superiority fostered through its dry intellectual engagement riddled with irony and realism. To be a cool and well-rounded reader is to be a reader of “lit fic.”

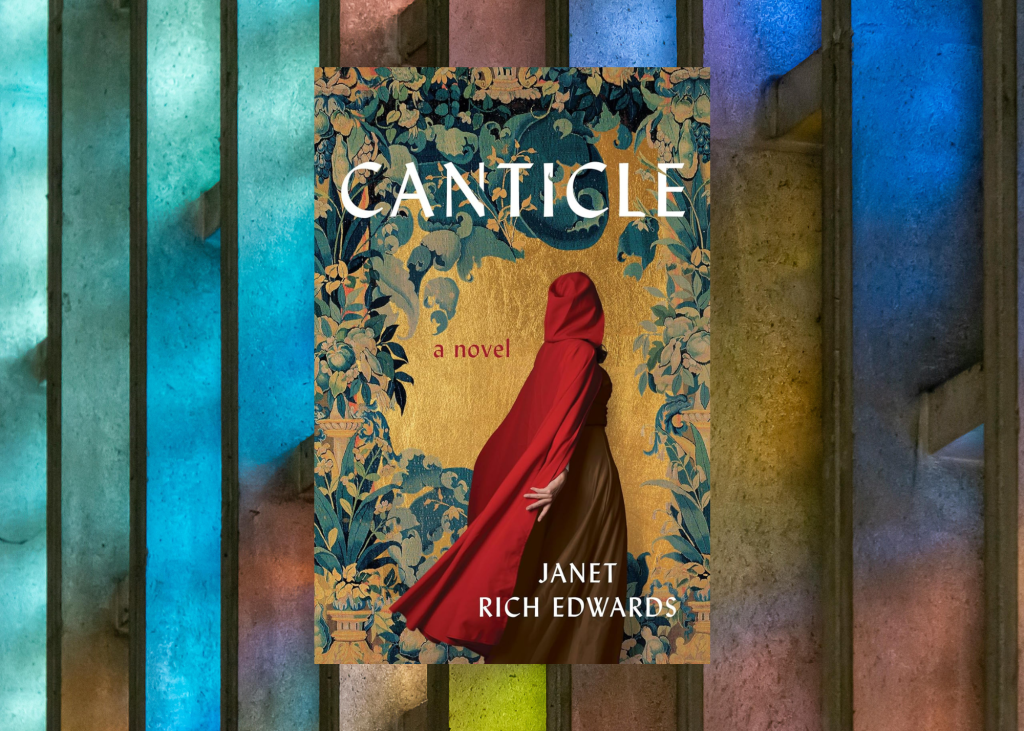

Canticle by Janet Rich Edwards is a breath of fresh air in this monogamous popular book culture. It is a story touched by the divine, the mystical, and the otherworldly aspect of hope that is absent in the mainstream genre.

Edwards’s debut novel follows Aleys, a teenage girl living in medieval Bruges, who is devoted to her faith yet is underserved by the Catholic Church’s patriarchal system. To escape an arranged marriage, she seeks solace with the Beguines, a community of laywomen who live independently from the church’s institution to practice their spirituality. Historically, this movement offered an alternative to marriage or cloistered convent life. Still, unfortunately, this fundamental escape from male-dominated spaces gave cause for the church to persecute these women as heretics, which is the fate foreshadowed for Aleys in the beginning of the novel:

“Witnesses will later swear the girl was lit like a taper, and some will claim she had a halo.”

The historical inspirations in the narrative enrich its already complex portrayal of women, particularly the Beguines, and in the references to female saints. It blows the dust off the medieval past and breathes life in an almost ethereal way, granting readers the earnest attempt to comprehend female agency in the 13th century. Aleys is characterized as a medieval woman, but she’s truly a woman of every century. Her restless search for purpose and community resonates outstandingly, and even though her spiritually devotional soul might not touch the hearts of all female readers, Aleys’s inherent difference and keen awareness of it are, in my opinion, universal.

Drawing on martyrs and mystics such as St. Catherine of Genoa, St. Clare of Assisi, and St. Teresa of Avila brings awareness to the persistence of women in patriarchal systems, specifically their persistence to be heard and understood. Their delicate dance between a saint and a heretic, simply because of their boldness in gender, is mirrored in Aleys and the way she seizes her situation through refusing to submit.

Although Canticle appears wrapped up in Catholicism, the story is not a fervently religious one. The novel parallels the bizarreness of sainthood to the peculiar condition of girlhood. Begging to be believed and not understanding what you are capable of because society reminds you of what you “lack” are touchstones that Edwards visits in her study of gender and faith. Aleys faces pressures to embody obedience and purity due to her femininity and mysticism. These parallel states of formation are skillfully observed as societal expectations that construct a never-ending climb to reach true fulfillment, allowing for themes of vulnerability and goodness be subverted.

Stylistically, Edwards’s prose and narrative structure gorgeously capture a time period that most readers are not well-versed in, and suddenly transport them there. They add another layer of obscure divinity while we follow Aleys’s journey to her martyrdom. Every print on the page is breathtaking as she faces down the dynamic between voice and silence, since saints are subjects of praise in Catholicism, but girls are expected to remain quiet. Even the title—a canticle is a song or hymn—references the power of voice and how one’s suffering can be turned into something beautiful for others to consume.

Canticle cleverly challenges the modern literary genre trends by embracing a lit fic fashion that provides a platform for silenced voices while infusing magic and hope that are largely absent today. Particularly, the novel’s images of girlhood significantly provide commentary that continues to be needed, calling on readers to examine how the past and the present may be more alike than we think, and that faith can be the one thing that simultaneously destroys and enlightens us the most.

Rating:

Image taken from Amazon

Leave a comment